© Mia Keinanen 2025

Martha Graham

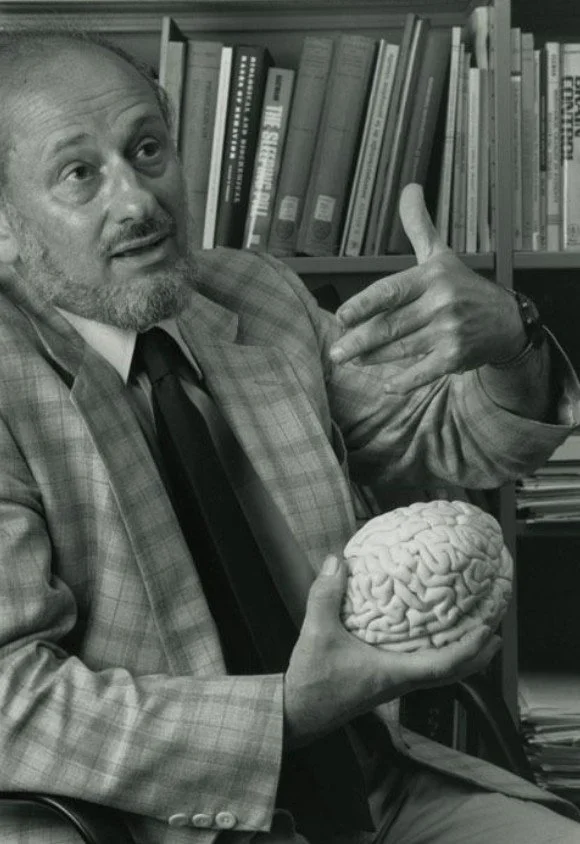

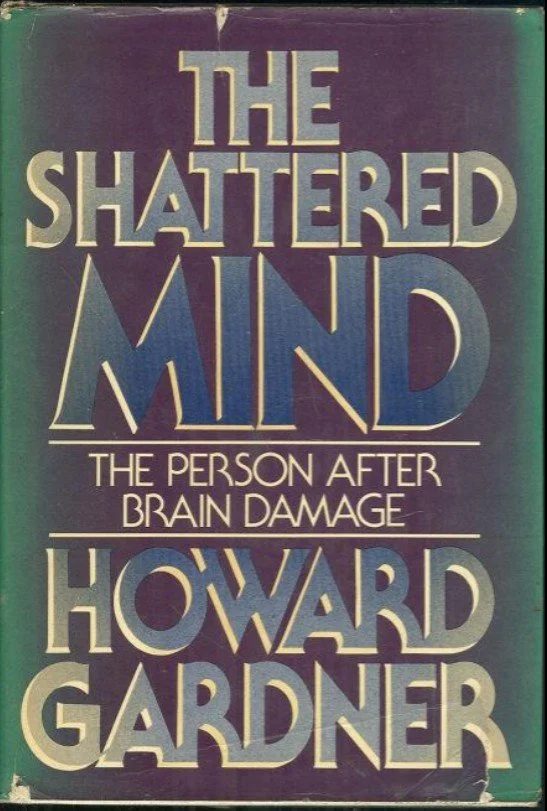

“The body never lies,” said Martha Graham, one of modern dance’s most eminent pioneers. Her company recently launched its centennial celebrations. Graham’s claim suggests that a person's movements and expressions will reveal their true emotions and intentions—even when words fall short. Indeed, according to Howard Gardner’s theory, our intelligences are multiple, each representing different ways of processing information and solving problems.

I want to tweak Howard’s formulation: What if the other intelligences (linguistic, logical-mathematical, musical, spatial, intrapersonal, interpersonal and naturalistic) cannot exist without the kinesthetic intelligence, without the human body? Indeed, in the race toward General Artificial Intelligence (AGI), this very quandary has been a major challenge. It’s been termed Moravec’s paradox: While AI can solve complex cognitive tasks, the sensorimotor capacity or the ability to generalize skills may be much lower than that of a child.

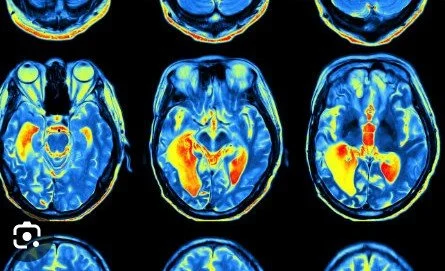

Case in point: Last year at the opening of MIT’s Quest for Intelligence (November 2024), an interdisciplinary center that probes how the brain produces intellect and how it could be replicated in artificial systems, a claim was made: “natural intelligence” still trumps artificial intelligence. By natural intelligence, they refer to kind of intelligence that biological organisms—especially humans—possess. Natural intelligence leverages sensory data to construct internal models of the world, enabling effective generalization from minimal information. Natural intelligence can make a lot from a little. In intriguing contrast, artificial intelligence, or Large Language Models (LLMs) make a little from a lot by synthesizing vast amounts of data succinctly.

The question arises: What if embodiment allows us to access deeper truths that are not expressed linguistically or mathematically? Indeed, as I construe it, cognition is contextual. It blossoms from our physical interactions with the world—put differently, the human body-in-context makes cognition possible. Yet, the human body is conspicuously absent from the LLMs that could make AGI possible. At the aforementioned conference, the mission statement proclaimed: “Imagine if we could build a machine that grows into intelligence the way a person does—starts like a baby and learns like a child…Imagine systems, like ChatGPT, which you could ask any question and expect to get reasonable answers—but inside they are not just black boxes trained on all of humanity’s data. Instead, they are our best current models of how human minds and brains think and communicate.” Assuming this stance: No human mind thinks or communicates without a body; the body is not there just to carry our heads around.

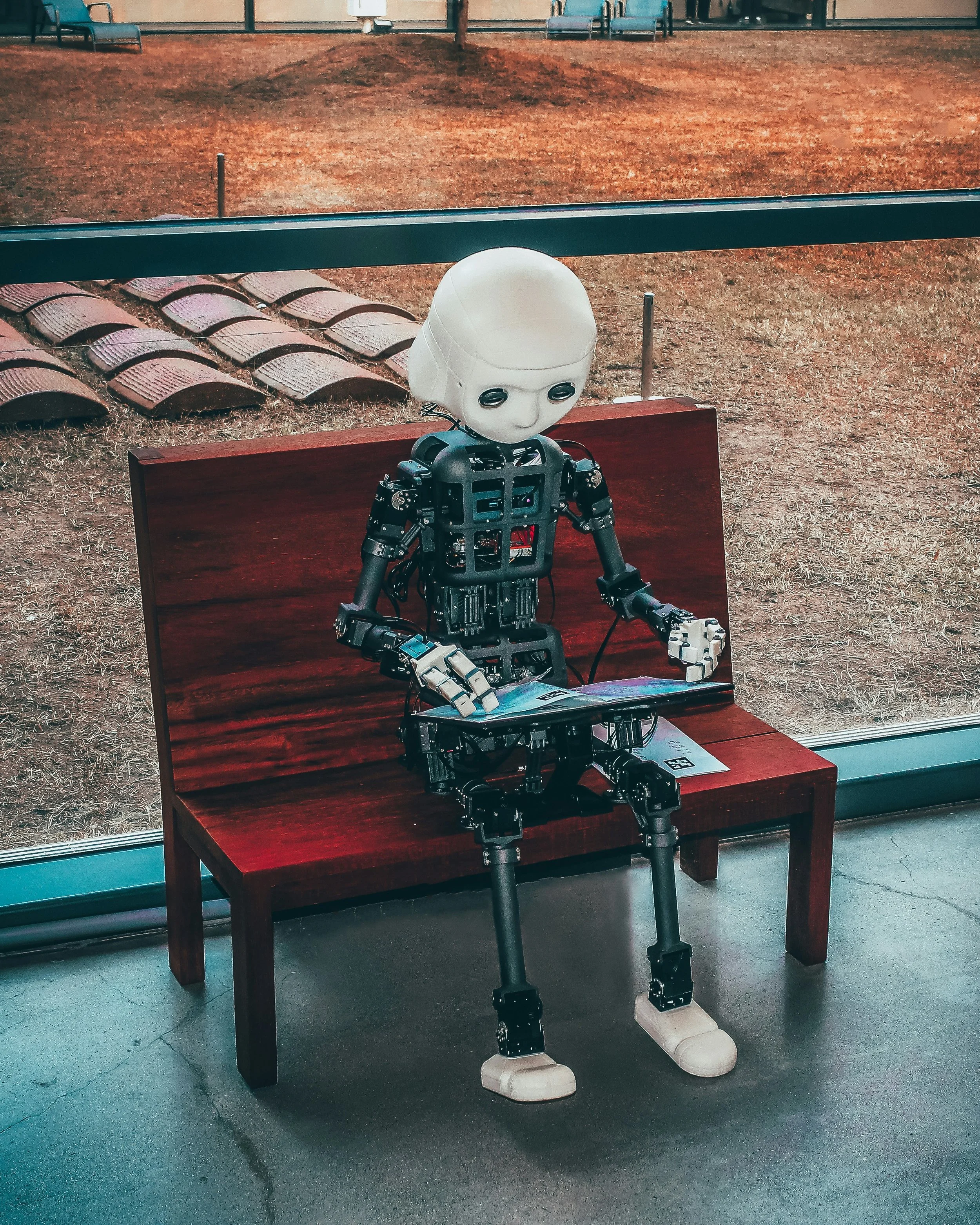

Boston Dynamics made a video of robots dancing to the song, “Do You Love Me?” (by The Contours)—and the presentation went viral. Their three kinds of robots (humanoid, robot dog, and warehouse robot) perform their dance moves in a synchronized manner. The feat required advanced robotics engineering, precise programming and sophisticated motion planning. 1X, a Norwegian humanoid robot start up, on the other hand, believes in building robots that have a “human form factor”. These entities adapt to the world humans have built and learn accordingly from humans by co-existing with us—just as a child does. We mere mortals have not seen these robots dance yet, but surely this’ll happen soon. (Children begin dancing as early as 9 months of age and many never stop!)

Neo 1X humanoid robot promotional photo

These contrasting examples foreground two schools of thought for the AGI effort. Boston Dynamics maintains that the internet already contains enough data—especially when paired with the vast amount of online video, massive computational power, and clever engineering—to eventually reach the holy grail of AGI. In contrast, 1X contends that true general intelligence requires direct interaction with the physical world. It requires learning through human form in the environment designed for humans.

Two weeks ago, 1X’s launch of the humanoid robot Neo sparked a global frenzy. Neo is designed to interact with humans in a highly lifelike and responsive manner; it is also soft and weighs only 114 pounds. Bernt Kristensen, the founder of 1X, also underscores that the robots must reflect human ethical values. Humanoid robots need to be accountable in how they engage with people and that human-robot interaction (HRI) should prioritize empathy and mutual respect.

Memes spread instantly, The Wall Street Journal put it on the front page, and The Daily Show with Jon Stewart roasted it—the ultimate badge of cultural relevance. Why the hype? For the first time, a humanoid robot opened for public preorders. With humanoids projected to become more common in households than cars, this marks a major milestone: the beginning of true human–humanoid coexistence, where we can finally learn from one another. Moreover, as humanoids learn by mimicking human actions and “learning by doing,” it could offer fresh insights into AI development—and possibly bring us closer to Artificial General Intelligence (AGI).

As a former professional dancer, (and also, one of Howard’s doctoral students), I believe that body and movement are not mere afterthoughts—they are fundamental to the nature of intelligence itself. What’s most fascinating about AI vis-à-vis kinesthetic intelligence is that AI has no body, and the body doesn’t compute—yet we humans do both. One mode is lost in ecstatic dance, the other in deep thought. Yet it’s the body’s movement that gave rise to cognition, which, no matter how abstract, remains grounded in the physical self. And the body does not know how to lie.

As Howard noted in his recent talk with Anthea Roberts, AI may replicate the disciplined, synthesizing, and even aspects of the creative mind—but the respectful and ethical minds remain firmly human responsibilities. I agree, AI requires the human element (feet on the ground) to anchor its power and potential in terms of real-world human values, needs, and concerns. The true value of AI is as a mirror—AI will not be about our escape, but rather our striving to grasp, know, and appreciate the human condition more deeply.

As Anthea Roberts pointed out, because AI is being trained on the vast pool of written and visual content available online, creative professionals need new strategies to protect their work. Indeed, this is a chilling point which urgently needs attention and resolution. I note that, for once, dance is not the lowest on the totem pole. It cannot be copied and reproduced as literature, visual art, and design can be—at least not in terms of live performance. As such, it’s not equally threatened by AI. I predict a boom in live performance and sports, as people seek out the thrill of watching trained human bodies do the extraordinary—raw, unpredictable, and beyond what machines or AI-generated TV series or movies can offer. We feel it in our bodies.

Humanoid robots may one day outshine us—not because they are us, but because they aren’t. Unbound by the limits of flesh, their movements may be flawless, their emotions simulated with precision. Yet for all that perfection, will we truly feel them? Perhaps, paradoxically, we’ll connect even more—drawn to an "upgraded" version of our own emotional blueprint. Either way, for now, I’ll take the fragile, fleeting beauty of a live dance—which, by the way, I’m off to see tonight.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For comments on earlier drafts, I thank Howard Gardner, Torkel Engeness, and Noah Riskin.

FOOTNOTE

“Natural intelligence” bears some similarity to what Howard Gardner has termed the “naturalist intelligence.” See Intelligence Reframed (1999) and other writings.