When The New York Times elects to devote more than a page to a news story (link here), that’s news in itself—even more so if the story is about psychological research.

On Tuesday, March 22, 2022, in the print edition of the paper, there was a major story on “decoding shapes” with the subtitle “Grasping geometrical concepts may make humans special.” The story describes the research of neuroscientist, Stanislas Dehaene, an expert on numerical and mathematical cognition.

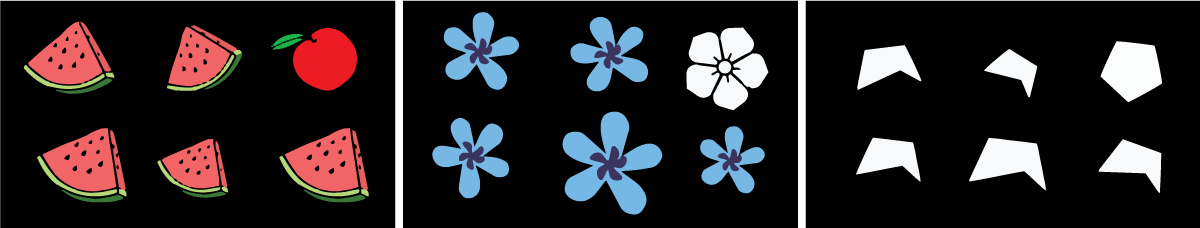

Dehaene and colleagues have demonstrated that human beings, but not baboons, can pick the “odd one out” when shown several instances of the same geometric shape (e.g., a five-sided irregular form presented in different sizes and orientations) along with a regular five-sided geometrical shape (e.g., a pentagon.) In other words, humans have the concept of regular vs. irregular shapes. When the same task required selecting a cherry as the odd one in the midst of images of watermelon slices, baboons had no trouble in doing so.

Here are the kinds of problems used to test baboons:

Image from The New York Times | Source: Mathias Sablé-Meyer, Stanislas Dehaene et al.

On this seemingly modest basis, Dehaene builds a vast superstructure. He says that human beings are capable of perceiving and creating geometric forms, and this capacity in turn enables them to construct systems for representing ideas—as is needed in creating artistic renderings, or geometric numerical systems. And since he introduced these ideas at a workshop at the Vatican last fall, he adds the following bold conjecture: “The argument I made in the Vatican is that the same ability is at the heart of our capacity to imagine religion.”

I’m less interested in the possible link between conceptions of geometric forms and conceptions of god (or, if you prefer, God) than in the fact that geometry is now being posited as a uniquely human capacity, just as language has been argued to be uniquely human by linguist Noam Chomsky. Over half a century ago, Chomsky marshaled a huge amount of evidence that linguistic capacity is an exclusively human faculty, and one that allows—via syntax—all kinds of relations to be expressed among objects, actions, and ideas.

Both Chomsky and Dehaene are arguing for a uniquely human capacity, and these two capacities probably overlap little if at all. Language and geometry have very different evolutionary histories and draw on very different neurological systems. Indeed, if any two human capacities merit separation, discursive language and geometric forms would be high on the list. (Music could be a third).

Just this line of thinking induced me, over forty years ago, to conceive of the human intellect as decomposable into separate cognitive systems. When I wrote about spatial intelligence, I had geometry in mind. When I wrote about linguistic intelligence, I had expressive and discursive language in mind. And when I wrote about logical-mathematical intelligence, I had in mind arithmetic, algebra, and logical reasoning.

It’s therefore revealing to me when The New York Times article ends with the following sentences:

“Language is often assumed to be the quality that demarcates human singularity, Dr. Dehaene noted, but perhaps there is something that is more basic, more fundamental. We are proposing that there are languages—multiple languages.”

Perhaps someday, he or his colleagues, will bite the bullet and say “multiple intelligences.”