Against this background, how have I re-considered or re-conceptualized the three issues that, as a scholar, I’ve long pondered?

Synthesizing is the most straightforward. Anything that can be laid out and formulated—by humans or machines—will be synthesized well by ChatGPT and its ilk. It’s hard to imagine that a human being—or even a large team of well-educated human beings—will do better synthesis than ChatGPT4, 5, or n.

We could imagine a “Howard Gardner ChatGPT”—one that synthesizes the way that I do, only better—it would be like an ever-improving chess program in that way. Whether ChatGPT-HG is a dream or a nightmare I leave to your (human) judgment.

Good work and good citizenship pose different challenges. Our aspirational conceptions of work and of membership in a community have emerged in the course of human history over the last several thousand years—within and across hundreds of cultures. Looking ahead, these aspirations indicate what we are likely to have to do if we want to survive as a planet and as a species.

All cultures have views, conceptions, of these “goods,” but of course—and understandably, these views are not the same. What is good—and what is bad, or evil, or neutral—in 2023 is not the same as in 1723. What is valued today in China is not necessarily what is admired in Scandinavia or Brazil. And there are different versions of “the good” in the US—just think of the deep south compared to the East and West coasts.

ChatGPT could synthesize different senses of “good,” in the realms of both “work” and “citizenship.” But there’s little reason to think that human beings will necessarily abide by such syntheses—the League of Nations, the United Nations, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the Geneva convention were certainly created with good will by human beings—but they have been honored as much in the breach as in the observance.

A Personal Perspective

We won’t survive as a planet unless we institute and subscribe to some kind of world belief system. It needs the prevalence of Christianity in the Occident a millennium ago, or of Confucianism or Buddhism over the centuries in Asia, and it should incorporate tactics like “peaceful disobedience” in the spirit of Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King, or Nelson Mandela. This form of faith needs to be constructed so as to enable the survival and thriving of the planet, and the entities on it, including plants, non-human animals, and the range of chemical elements and compounds.

Personally, I do not have reservations about terming this a “world religion”—so long as it does not posit a specific view of an Almighty Figure—and require allegiance to that entity. But a better analogy might be a “world language”—one that could be like Esperanto or a string of bits 00010101111….

And if such a school of thought is akin to a religion, it can’t be one that favors one culture over others—it needs to be catholic, rather than Catholic, judicious rather than Jewish. Such a belief-and-action system needs to center on the recognition and the resolution of challenges—in the spirit of controlling climate change, or conquering illness, or combatting a comet directed at earth from outer space, or a variety of ChatGPT that threatens to “do us in” from within….Of the philosophical or epistemological choices known to me, I resonate most to humanism—as described well by Sarah Bakewell in her recent book Humanly Possible.

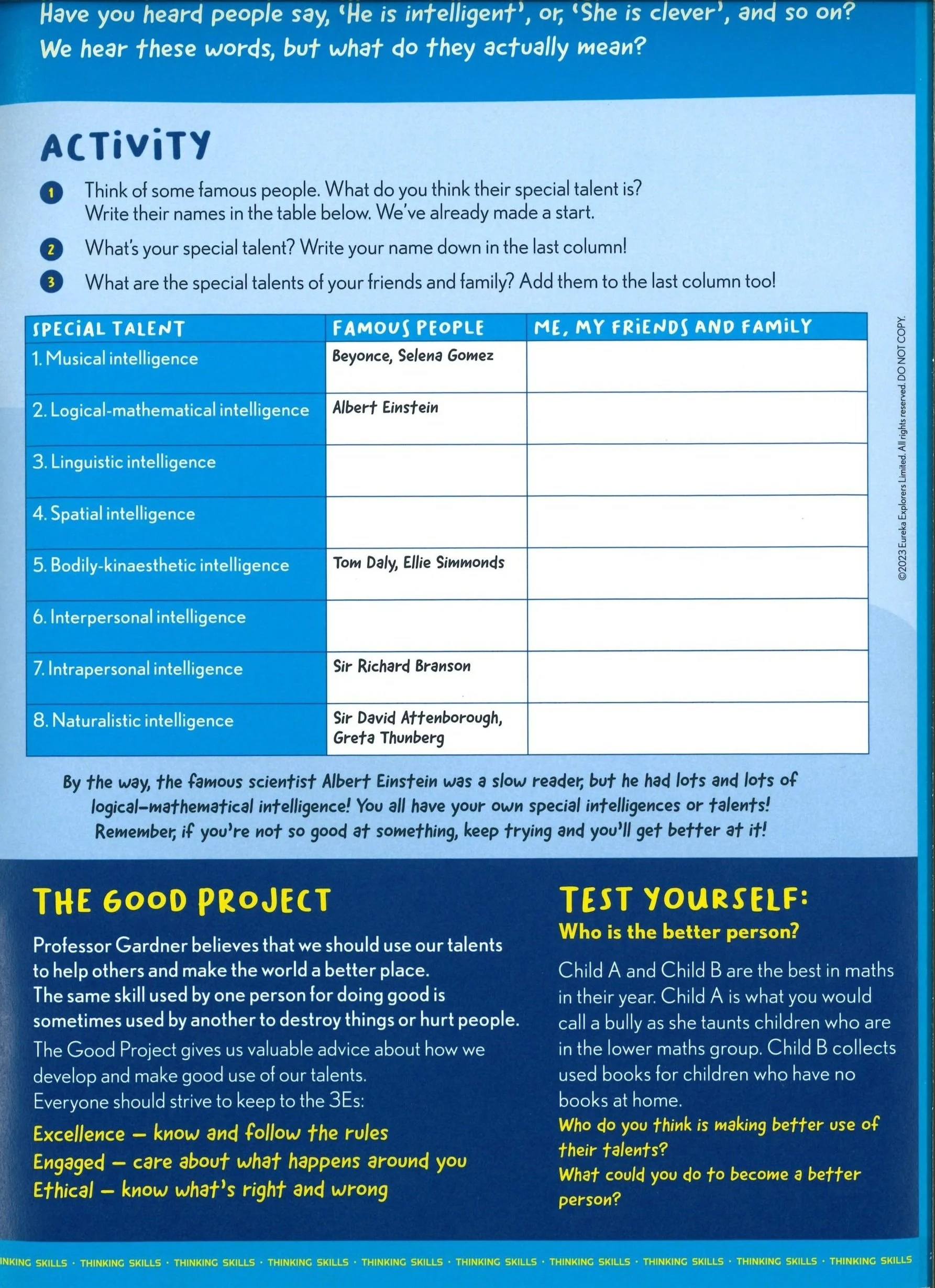

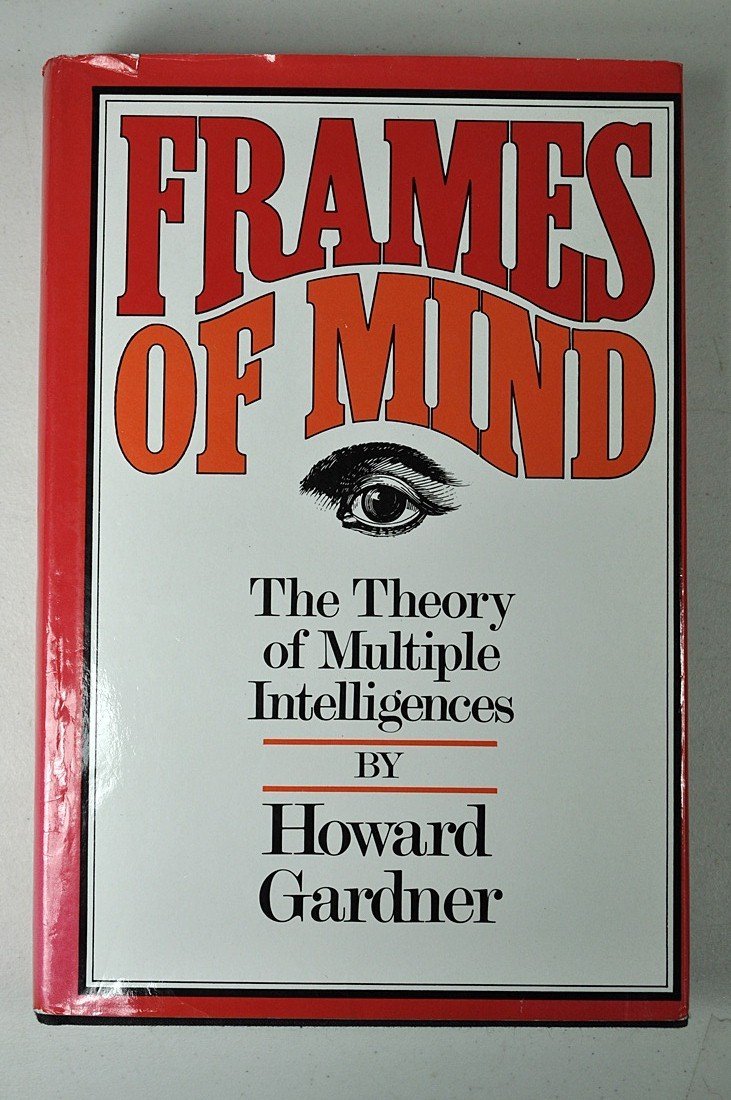

Multiple Intelligences (MI)

And, finally, I turn to MI. Without question, any work by any intelligence, or combination of intelligences, that can be specified with clarity will soon be mastered by Large Language Instruments—indeed, such performances by now constitute a trivial achievement with respect to linguistic, logical, musical, spatial intelligences—at least as we know them, via their human instantiations.

How—or even whether —such computational instruments can display bodily intelligences or the personal intelligences is a different matter. The answer depends on how broad a formulation one is willing to accept.

To be specific: