By Shinri Furuzawa

New computer algorithms are developing personal intelligences and are capable of outperforming us at games requiring skills once thought to be specific to humans. For decades, computers have surpassed us at games which are primarily logical, syntactic, or mathematical, such as chess, or Go.

Now, however, a recent article in Science describes the Cicero algorithm which can win against humans at the board game, Diplomacy. Enjoyed by the likes of John F. Kennedy and Henry Kissinger, this is a game which requires intuition, persuasion, and deception. Cicero is able to discuss strategy, forge alliances, and carry out subterfuge and betrayal. It mimics natural human language in text conversations that entail negotiation with other players. The ability to observe and evaluate the trustworthiness of other players while convincing others of one’s own trustworthiness, and dealing with imperfect information, are key skills for actual human diplomats.

All things considered, one wonders how close AI could come to replicating the skills of a real diplomat and whether one day, AI could even replace human diplomats.

What Makes a Good Diplomat?

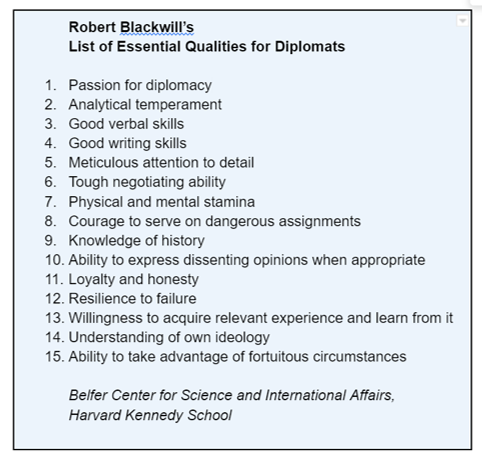

Former high-level American diplomat Robert Blackwill, suggested fifteen qualities which he thought essential for diplomats. Perhaps a third of these characteristics are inherent, and therefore irrelevant to AI, such as resilience to failure, or honesty. In other areas, such as analytical skills, attention to detail, or knowledge of history, AI already surpasses humans.

AI would, however, struggle in any area involving interactions that occur in person when the personal intelligences are especially vital. Diplomats must accurately collaborate, observe and evaluate others, and understand other people’s motivations while taking into account cultural, political, organizational and other differences. These trained professionals form mental models of their antagonists, and update them even unconsciously.

Diplomats are also skillful in interpreting non-verbal cues such as facial expressions, eye movement, and body posture. For decades, it has been common for diplomats to receive specific instruction on these interpersonal skills. While AI has made advances in interpreting non-verbal cues and information, it’s not quite there.

Facial and emotional recognition: AI is already being used to recognize faces and monitor people’s facial expressions, for example, in airport security systems. The problem for affect detection algorithms arises, however, with the fact that facial expressions of emotion are not universal; the way in which people communicate their emotions can vary according to culture or the situation. AI also performs better at recognizing Caucasians over people of color, a further problem that may lead to racial profiling.

If AI can’t yet read us well by looking at our faces, it does better at listening to our voices.

Voice analysis: AI already has voice recognition and realistic voice generation. It can now also be used to detect patterns and characteristics in the voice that cannot be picked up by the human ear. Algorithms can predict psychiatric illness and other health conditions. By analyzing recordings of Vladimir Putin’s voice in February and March of 2022 during the ongoing war in Ukraine and comparing them to a recording of a talk he gave in September 2020, AI was able to detect stress levels 40% above baseline. While AI can collect such data, it must still be interpreted by humans and cannot—or at least should not—be used to predict human behavior.

AI capabilities may still be nascent in some areas, but they will only improve in the future.

Could AI RENDER Human Diplomats OBSOLETE?

Diplomacy may involve skills that we have long considered to be quintessentially human. I talked to Steven Siqueira, a former Canadian diplomat and chief of staff for several UN peace operations, and to Dr. Martin Waehlisch who leads the Innovation Cell in the Policy and Mediation Division of the UN Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs. I asked them what a diplomat does that an AI could never do. It seems to me, that it comes down to interpersonal intelligence.

Steven Siqueira - former Canadian diplomat and chief of staff for several UN peace operations

Martin Waehlisch - leads the Innovation Cell in the Policy and Mediation Division of the UN Department of Political and Peacebuilding Affairs

Developing personal relationships: In Siqueira’s view, “You need personal relationships to get things done.”

He gave the example of when he was tasked with establishing a UN mission in Sudan. Siqueira negotiated with a high number of separate stakeholders, which meant cultivating a myriad of different relationships. AI may be able to form analyses and identify requirements, but actual implementation is a human task. It would be extremely hard for AI to navigate the interface between personalities, and the intricacies behind each stakeholder’s position: their limitations and accountability whether it be to politicians, the military, civil society, or the media, all while working together towards a mutually satisfactory outcome.

Political scientist, Joseph Nye, would agree on the value of human relationships. Nye describes the importance of “soft power” as opposed to traditional “hard power” which relies on military or economic strength. He suggests that agreements and alliances today are fostered more through amicable relations, using tact and warmth, rather than aggressive tactics. According to Nye, even a smile can be a soft power resource. Diplomatic efforts need to be directed at citizens, not just governments, shifting to influence through likeability, attraction, and relationship rather than power—or at least in addition to—force, or coercion. As Waehlisch says, “The future is about soft skills… I was skeptical of emotional intelligence but I’m more and more convinced.”

Innovative thinking: AI’s ability to think creatively and adapt to circumstances is also questionable. AI cannot respond in innovative ways if it is only drawing from the past. In the Diplomacy game, the chatbot is not creating anything new, it’s regurgitating based on percentages of success rates in past games.

In the real world, diplomats think on their feet and rely on their training and experience to deal with new situations. This aligns with the last point on Blackwill’s list; diplomats must be quick to recognize opportune moments and know how to exploit fortuitous and unforeseen circumstances when they arise.

Experience: In diplomacy, experience is crucial. Diplomats are trained through mentoring and vital skills are learned on the job. Blackwill listed learning from experience as an essential skill for diplomats, and as he puts it,“Would you hire a plumber who was academically well-versed in water distribution, but had never installed a pipe?”

What Role Does AI Have to Play in Diplomacy?

AI may fall short in personal intelligences, but it fares significantly better in linguistic and logical-mathematical intelligences. Siqueira and Waehlisch provided some insights into how AI is being used in diplomacy now, and how it could be used in the future.

Generating text: Blackwill’s list of essential skills includes the ability to write and speak well, or linguistic intelligence. The latest reports on Open AI’s ChatGPT-3 attest to AI’s ability to converse convincingly with a human. It can engage in philosophical discussions, tell (bad) jokes, and debate political issues; it can also write and debug code, write college-level essays, and take tests successfully. Whether the task entails making an after-dinner speech or giving a presentation, AI can be programmed to tailor language, tone, style, format to match an audience. Many of the more mundane report-writing tasks performed by interns today could be carried out by AI. Diplomats will no doubt increasingly rely on AI for research.

Mediation: AI could be used to support mediation. At the UN, for example, all mediated agreements are in a database. AI could easily draw upon the same language to mitigate similar situations that have occurred in the past. AI could scan and track different clauses—thereby providing valuable insights and perhaps helping to sustain peace efforts.

Advisory roles: Computers are able to process and instantly retrieve exponentially more information than humans, enabling them to take over traditional advisory roles. Diplomats on the UN Security Council use their smartphones to find information or receive instructions rather than relying on advisors to whisper in their ears. Computer programs and algorithms are superior at assessing data and anticipating outcomes—important skills in negotiation.

Targeting resources: At the UN, AI capacities in the form of data aggregators are already being used to analyze the press releases and communiques of all foreign ministries, allowing political officers to “mine the sentiment” on a given topic. Knowing which countries are most concerned about an issue enables targeted approaches—for example, by knowing which countries may be open to providing donor resources.

Geospatial technology has recently made significant advances in providing “eyes in the sky.” These capacities entail data collection and analysis in fragile states which can improve monitoring and allow targeted humanitarian or peacekeeping efforts. It’s important to remember, however, that early warning doesn’t mean early action–political decision-making must still be done by people. Technology can’t fill this gap.

Increased productivity: AI undoubtedly improves productivity. It offers internal solutions by tackling intrinsic systemic challenges with products aimed at automation and speed. External solutions enable closer human connections which results in inclusivity.

Access: AI also enables dialogue. Many groups that once could not have been part of the negotiation process due to geographical remoteness, or that were simply not allowed at the table, can now be party to the conversation. Increased opportunities in terms of language and translation capabilities through TV and radio mining enable access to low-resource languages. Such outreach outflanks cultural and language barriers.

Training intrapersonal intelligence: New advances in virtual reality (VR) can be used to develop a diplomat’s intrapersonal intelligence. Such technology allows active “body swapping,” so people can “walk each other’s journeys.” Built-in behavioral science experiments may well detect implicit biases and identify cognitive challenges. VR provides a safe space for diplomats to learn about themselves, discover their biases, and better understand their interactions with others. Put differently, it fosters perspective-taking and helps overcome dehumanization. As Waehlisch suggested, “What if Netanyahu went through an Israeli checkpoint as a Palestinian?” In VR, he would see how people looked at him, the weapons pointed at him, and feel the danger, to perhaps reveal a new perspective.

Dangers of AI in Diplomacy

There are some things that can never be left to AI.

Decision making: Delegating decision-making to AI would be a mistake, even though in some ways it could be seen as desirable.

It is conceivable that AI could be programmed to make more rational, fair, and evidence-based decisions than humans. After all, AI is not vulnerable to human emotions or weaknesses. For centuries, the ideal diplomat was like a robot, coldly efficient, rational, and devoid of emotion, as codified in diplomatic protocols. Indeed, diplomats are routinely rotated every few years to prevent emotional attachments. In contrast, AI has no problem remaining detached and calm in stressful situations. Without emotions or physical sensations, AI could not be threatened or made to feel vulnerable in the same way as a human, for example, as when Vladimir Putin used his dog to intimidate Angela Merkel—famously terrified of dogs. AI would not be motivated by personal gain, or be tempted to abuse its authority and would be untroubled by the personal cost of resisting political pressure and standing by diplomatic policy decisions (in a nation’s interest) even if unpopular. AI would not be susceptible to exhaustion or lapses in judgment. In fact, a survey conducted by the Center for the Governance of Change at IE University in Spain, one in four Europeans indicated that they would prefer policy decisions be made by AI rather than politicians. However, in decision-making complete rationality is not always best.

Take as an example, the “Prisoner’s Dilemma” from game theory. Even though mutual cooperation would yield a greater net reward, the only possible outcome for two purely rational prisoners is betrayal. And of course, in real life, this stance could quickly lead to escalated military action, or nuclear war and mutual destruction. Even if we set parameters beforehand, these may be incomplete or fail. Would AI have the ability to pull back? If an algorithm were tasked with bringing about world peace, an efficient move might be to eradicate all humans from the planet.

Yejin Choi, a computer scientist and 2022 recipient of the MacArthur “Genius grant,” makes the same point from an ethical standpoint. In one interview, she said that in the most fundamental ways, “AI struggles with basic common sense.”

While humans understand many things, such as common exceptions to rules, AI must be specifically taught, or be at risk of choosing extreme or damaging solutions that humans would never consider. Choi argues the challenge will be to account for value pluralism, to teach AI that values can be broad and that diverse viewpoints need to be taken into account. Ethical guidelines are necessary but there is no one moral framework that can be imposed. The implications for diplomacy are dangerous. While AI will continue to improve, Choi doubts that humans will ever create sentient artificial intelligence, or AI with true intrapersonal intelligence.

Malevolence: There is potential for AI technology to be used maliciously. We need to work on ways to forecast and mitigate such threats. The threat of AI is easy to see in what has been described as today’s “post-truth era.” AI is being used for negative messaging which leads to greater polarization, destabilization of existing frameworks, and the influencing of elections.

Bias: There is also the problem of bias in AI systems. While often seen as a technical problem, most AI bias stems from human biases and systemic, institutional biases. For machine learning models to work well, a very large and diverse, and robust set of data involving all ages, genders, ethnicities, and other demographic criteria must be used. In the history of Western diplomacy, key decisions have been made by mostly men of a certain profile which could certainly skew the dataset. Regulations and safeguards are of course necessary. Excessive concentration in AI space and in a handful of technology companies must also be avoided through regulation—for example, encouraging competition and not allowing monopolization.

“The Greatest Threat and the Greatest Opportunity”

French Ambassador, David Cvach, said in a 2018 Tedx talk that AI is both the greatest threat and the greatest opportunity for diplomacy. There is truth to this assertion.

Sophia robot

In the field of international relations and diplomacy, AI is touted more often as a threat, for example, in terms of autonomous weapons. Though AI may have (often unintentional) negative consequences, organizations such as AI For Peace have a different stance: on their account, dialogue between academia, industry and civil society can help ensure the benefits of AI while minimizing the risks. Waehlisch has suggested machine learning and natural language processing can be used to promote peace. His chief concern is how to use new technologies to help de-escalate violence and increase international stability.

I would argue that while AI will augment the work of human diplomats making them more efficient and effective, it will never be more than a useful tool in diplomacy. Indeed, it could not and should not replace human diplomats. AI might outperform humans at most analytical tasks, but humans will still surpass AI at more subtle, “feeling tasks.” Even as algorithms come closer to replicating human interpersonal intelligence, direct person-to-person interaction is probably the most important method of increasing or maintaining “soft power” in diplomacy. Chatbots may be able to fool humans at the Diplomacy game online, but robots such as Sophia (appointed in 2017 as the UN Development Program’s first Innovation Champion), could not yet be mistaken for human.

On the positive side, the opportunities of AI lie in creating a more level playing field, as long as technology is not limited to wealthy countries. The ability of diverse stakeholders to use algorithms could provide more holistic and comprehensive solutions to today’s challenges, such as forced migration or unanticipated pandemics. Perhaps AI can be a means for engaging and uniting people around the world on issues of mutual interest for a more peaceful and sustainable future. We should use all our multiple intelligences, and the possibilities of artificial intelligence, to achieve this end.

In our next blog post, Howard Gardner will discuss the implications of AI in understanding human personal intelligences.

I would like to thank Howard Gardner for his valuable input into this post. I am also grateful to Steven Siqueira and Martin Waehlisch for very kindly agreeing to interviews and sharing their thoughts.